Today’s question comes from Western Australia. My correspondent says:

There was recently a discussion regarding the administration of sedation to patients being transported under the Mental Health Act in WA. In that discussion, a circular came to light which contained the following quote:

Due to changes in the current Mental Health Act 2014, Paramedics are no longer authorised to independently administer sedation to patients who are the subject of a transport order under the Act without specific authorisation from a doctor, preferably the patient’s discharging doctor.

The circular goes to require that paramedics receive “clear instructions from the discharging doctor allowing you to administer sedation where clinically necessary…” and to administer that sedation as per CPGs.

As far as I can tell, the Mental Health Act 2014 doesn’t make reference to “sedation” or “paramedic”, so I’m curious as to if this guidance is actually due to the Act, or rather just an internal policy.

In particular I think it’s curious to require that a paramedic receives authorisation from a doctor to do something that is “clinically necessary” – my reading of your previous posts has lead me to believe that paramedics should not need explicit authorisation from a doctor to do what is clinically necessary.

I have been provided with a copy of the circular dated 24 February 2017. I’m told that the Clinical Services Director, when asked what prompted the circular, replied:

Patients who are detained under the mental health act can only be sedated under “emergency psychiatric treatment” section of the act, and the only type of person who can authorise this is a doctor. The authorisation must be specific to a particular patient, not generic as our CPGs are.

Whether people other than doctors can independently apply “emergency psychiatric treatment” to a patient detained under the mental health act was specifically debated in parliament during the passing of the relevant legislation and the answer was “no”.

We have legal advice to this effect.

We believe that it is not sensible to sedate these patients under our behavioural CPGs, given the law.

We think that the treating doctor in the originating facility is the best person to authorise us in the event that it may be necessary during the transport phase between hospitals (& the doctor is not going to be present).

The Mental Health Act 2014 (WA) came into effect on 30 November 2015. It has been amended by the following Acts:

| Name of Act | With effect from |

| Mental Health Legislation Amendment Act 2014 | 30 November 2015 |

| Mental Health Amendment Act 2015 | 30 November 2015 |

| Health Services Act 2016 | 1 July 2016 |

| Local Government Legislation Amendment Act 2016 | 21 January 2017 |

| Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (WA) Amendment Act 2018 | Not yet in force. |

It is unclear which ‘changes’ the circular is referring to but given that it is dated February 2017 one might infer that it’s the changes in the Local Government Legislation Amendment Act 2016 that came into force on 21 January 2017. The Local Government Legislation Amendment Act 2016 inserted the words ‘a local government, regional local government or regional subsidiary’ into the definition of ‘state authority’ in s 572. That change is clearly not relevant to the issue of sedating patients.

The Health Services Act 2016 amended the Mental Health Act 2014 by deleting references to the Hospitals and Health Services Act 1927 and referring, instead, to the Health Services Act 2016 or, in s 348, the Private Hospitals and Health Services Act 1927. These changes also did not relate to the sedation of patients.

The other changes were all made before the 2014 Act came into force so they were incorporated into the Act at the time of commencement. They couldn’t be described as ‘changes in the current Mental Health Act 2014’. I therefore have no idea what the circular is referring to. There have been no relevant changes since the Act commenced on 30 November 2015.

Does the Mental Health Act 2014 say what the circular and advice say it does?

Transport orders

The Act refers to a ‘transport officer’ that is ‘a person, or a person in a class of person, authorised under section 147 to a carry out a transport order’ (s 4). The regulations prescribe that the class of persons who are transport officers are those people employed by agencies that have entered contracts with WA Health to provide mental health transport services. I do not know if St John (WA) is a contracted transport provider.

The Act also provides for transport orders. A medical practitioner can make a transport order, authorising a transport officer to transport a mentally ill person, when:

- The person needs referral for examination at authorised hospital or other place (s 29);

- Where a person has been examined at a place that is not an authorised hospital and needs transport to a general or authorised hospital (s 63);

- Where a mentally ill person has been receiving medical or surgical treated at a general hospital and can now safely be transferred to an authorised hospital (s 67);

- Where a mentally ill person needs to be transferred from one authorised hospital to another authorised hospital (s 92); and

- Where a mentally ill person is granted leave to attend a hospital for medical treatment or who has had their leave cancelled and needs transport back to hospital (s 112);

- Where a person has failed to comply with a community treatment order and failed to attend upon a psychiatrist when directed to do so (s 129);

- Where a community patient requires to be detained in hospital (s 133);

- Transfer to and from an interstate mental health service (s 556);

- Transport of a community treatment patient to an interstate mental health service (s 560).

Where a transport order is made (except under ss 556 and 560) the provisions on making a transport order apply. Those provisions say, relevantly, that a transport officer, or in some cases a police officer (s 149) is to transport a patient in accordance with the order. The transport order allows the transport officer or police officer to apprehend and detain the person until they are received into the hospital (s 149).

Section 156 provides that police may detain a person who is suspected of being mentally ill and who needs detention in order to ‘protect the health or safety of the person or the safety of another person; or prevent the person causing, or continuing to cause, serious damage to property’.

These provisions say nothing at all about the use of sedation. In fact the terms ‘sedate’, ‘sedation’ or ‘sedative’ do not appear in the Act.

Emergency psychiatric treatment

The provisions dealing with “emergency psychiatric treatment” are found in ss 202-204. Section 202 says:

Emergency psychiatric treatment is treatment that needs to be provided to a person —

- to save the person’s life; or

- to prevent the person from behaving in a way that is likely to result in serious physical injury to the person or another person.

Section 203 says ‘A medical practitioner may provide a person with emergency psychiatric treatment without informed consent being given to the provision of the treatment.’ Again it doesn’t mention sedation or give particular authorisation for the use of sedation.

The Criminal Code (WA)

The Criminal Code (WA) s 243 says:

It is lawful for any person to use such force as is reasonably necessary in order to prevent a person whom he believes, on reasonable grounds, to be mentally impaired from doing violence to any person or property.

Hansard

Dr K.D. Hames, the then Minister for Health said in the Second Reading Speech (Hansard, Legislative Assembly, 23 October 2013, p. 5396)

Treatment decisions must always be made in the best interests of the patient. Voluntary patients, including people who have been referred for an examination by a psychiatrist, can be given treatment only with informed consent. There is an exception for emergency psychiatric treatment such as medication, which can be administered only to save the person’s life or prevent the person from behaving in a way that is likely to result in serious physical injury to the person or another person.

There were other contributors to the debate but a search of the Hansard did not reveal other uses of the term ‘emergency psychiatric treatment’. It might be inferred that this debate says that only medication can be given under the emergency psychiatric treatment provisions, but that is not what the Act says.

The Guardianship and Administration Act 1990 (WA) s 110ZH provides that a health professional can provide emergency care. A health professional is one of the 14 registered professions under the Health Practitioner National Law that, as of today, does not include paramedics. It also includes ‘any other person who practises a discipline or profession in the health area that involves the application of a body of learning’ (s 110ZH and Civil Liability Act 2002 (WA) s 5PA). This broad definition may extend to paramedics. That is a point of difference – the Guardianship and Administration Act says any health professional can provide urgent medical care without consent, whereas the Mental Health Act refers only to a medical practitioner given urgent psychiatric treatment. That would support an interpretation that only a medical practitioner can authorise sedation.

But even so treatment without consent has to be given by others, otherwise a person doing first aid would be guilty of an offence.

Discussion

I note that the circular says ‘Paramedics are no longer authorised to independently administer sedation to patients who are the subject of a transport order under the Act without specific authorisation from a doctor, preferably the patient’s discharging doctor.’ As noted transport orders can be made in many circumstances to authorise a transport officer to transport the patient. Where a person is subject to a transport order then they have seen a medical practitioner. The circular also notes that ambulance officers should complete ‘the inter-hospital transfer form…’ again demonstrating that the circular is not addressing a situation where ambulance are treating a mentally ill person as part of ambulance emergency response.

It is not clear however whether the authority suggested exists. The circular suggests that doctor’s be asked to write ““The use of sedation as per SJA CPG 2.5 – Disturbed and Abnormal Behaviour – is approved for this patient in the event that other, less restrictive measures have failed.” A medical practitioner can administer emergency care but that doesn’t mean he or she can authorise others to do it. A doctor may prescribe medication and allow others to administer it but on this advice they are leaving it to the ambulance paramedics to make the clinical judgment that the sedation is clinically indicated.

In the case where ambulance are responding to a triple zero call and determine that a person is mentally ill and needing care, that person is not subject to a transport order nor an ‘inter-hospital transfer’ and the circular does not appear to apply.

The advice of the Clinical Services Director is also talking about inter-hospital transfer. The advice says

We think that the treating doctor in the originating facility is the best person to authorise us in the event that it may be necessary during the transport phase between hospitals (& the doctor is not going to be present).

Again that is not referring to a person in the community who needs urgent care.

There could be some support for the view that paramedics can never, even when first responders, sedate a patient. That would require a conclusion that the only justification for paramedics provide medical treatment without consent is because they are a health professional within the meaning of the Guardianship and Administration Act. And, because the Mental Health Act provides that only a medical practitioner can provide urgent psychiatric treatment then that does not include ambulance officers. That seems to me to be a very conservative view and would mean that paramedics also couldn’t treat and transport any person who was mentally ill but could not consent to that care, even if they were compliant and did not require sedation.

As noted previously there is the common law doctrine of necessity that says medical care can be provided. In In Re F [1990] 2 AC 1 Lord Goff said:

The basic requirements, applicable in these cases of necessity, that, to fall within the principle, not only (1) must there be a necessity to act when it is not practicable to communicate with the assisted person, but also (2) the action taken must be such as a reasonable person would in all the circumstance take, acting in the best interests of the assisted person.

It would be my view that where a person is mentally ill and unable to consent then, at common law, a paramedic could treat and transport them just as they can for a person is unconscious or otherwise unable to consent to physical treatment. If the use of sedation is the care a reasonable paramedic would take as it was in accordance with the clinical practice guidelines then it would be justified. To the extent that it was necessary the provision of the Criminal Code (s 243) could also be called into to support those actions on the basis that the use of chemical sedation is a use of force.

Of course that doesn’t address the issue that employees and volunteers with St John (WA) are required to comply with the reasonable directions of their employer and if that is what St John require then that should be complied with. The difficulty will be when paramedics are registered if they feel constrained to provide less than optimal care to their patients. Their desire to treat the patients would not justify breaking the law if the St John interpretation is correct; but it may well give impetus to challenge the circular and to clarify why that is the St John view and what is their view when responding to an emergency call or when the patient’s condition changes during transport.

POSTSCRIPT

After writing the post, above (at 11.30pm at night) I thought that I had made some assumptions or not left the limited application of my conclusion clear enough. Given this is a very important issue for both paramedics and the mentally ill, I want to add some more comments.

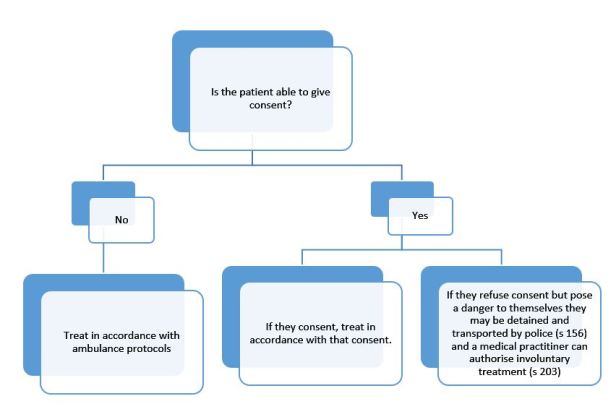

First, just because a person is mentally ill it does not mean that they are unable to make medical decisions and give, or refuse, consent. The aim of mental health legislation is to ensure that the mentally ill are involved in decision making as much as possible and where they are competent to make decisions, those decisions are respected. I would define ‘involuntary treatment’ as treatment given to a person who is mentally ill, competent and who has refused treatment, but is to be treated contrary to that refusal. That is different to a person who by reason of their mental illness or for any other reason, is unable to consent. The flowchart below may help explain that thinking:

My conclusion, that paramedics could provide clinically warranted treatment was limited to the situation where the person was unable to give, or refuse consent. Paramedics have no authority to treat a person who is mentally ill, would benefit from treatment but who is able to and has refused consent to that care.

With respect to a person who is threatening violence to another there is power to use force to restrain them. One would typically think of physical restraint and that will be the limits of most people’s authority. Arguably the use of sedation in accordance with clinical practice guidelines is just an example of the use of force but a prudent paramedic may wish to avoid that path at least until police are there but circumstances will determine that. If the person can’t be contained by other means and is an immediate and direct threat to themselves or others I would suggest that sedation is or could be an example of ‘reasonable force’.

Where police attend and take action under s 156, they may use reasonable force (s 172) and may ask others (eg paramedics) to assist. Again if there was simply no less invasive way to restrain a person in order to make it safe for them and the treating paramedics, sedation could be a use of ‘reasonable force’ to allow the person to be detained and transported as authorised by s 156.

In all these circumstances I’m talking about ambulance being involved as first responders to a mental health emergency. The circular, and the advice from the Clinical Services Director don’t address that issue. They are talking about a person subject to a transport order and ‘the transport phase between hospitals’.

Second, in my post above I’ve relied on the common law and the decision in In Re F. Western Australia (like the NT and Queensland) has a criminal code. The theory is that all the criminal law is found in the code rather than common law principles. The common law of necessity may be a defence to a civil claim but may not apply in a criminal case. Section 25 of the Criminal Code (WA) says:

(2) A person is not criminally responsible for an act done, or an omission made, in an emergency under subsection (3).

(3) A person does an act or makes an omission in an emergency if —

(a) the person believes —

(i) circumstances of sudden or extraordinary emergency exist; and

(ii) doing the act or making the omission is a necessary response to the emergency;

and

(b) the act or omission is a reasonable response to the emergency in the circumstances as the person believes them to be; and

(c) there are reasonable grounds for those beliefs.

That is akin to the common law doctrine of ‘necessity’ (though it is limited to an emergency), but where a paramedic was responding to a person with a mental health crisis, and the person could not give or refuse consent, this section would provide a defence to treating the person in accordance with ambulance guidelines.

Section 259 says:

A person is not criminally responsible for administering, in good faith and with reasonable care and skill, surgical or medical treatment (including palliative care) — (a) to another person for that other person’s benefit; or (b) to an unborn child for the preservation of the mother’s life, if the administration of the treatment is reasonable, having regard to the patient’s state at the time and to all the circumstances of the case.

Again that would justify paramedics treating a mentally ill person who could not give consent to their treatment. It would not justify giving treatment to a patient who can, and has, refused consent to treatment.

Section 262 says:

It is the duty of every person having charge of another who is unable by reason of age, sickness, mental impairment, detention, or any other cause, to withdraw himself from such charge, and who is unable to provide himself with the necessaries of life, whether the charge is undertaken under a contract, or is imposed by law, or arises by reason of any act, whether lawful or unlawful, of the person who has such charge, to provide for that other person the necessaries of life; and he is held to have caused any consequences which result to the life or health of the other person by reason of any omission to perform that duty.

Finally s 337 says:

Any person who detains, or assumes the custody of, a person suffering from mental illness (as defined in the Mental Health Act 2014 section 4) or mental impairment, contrary to that Act or any law relating to mental impairment, is guilty of a crime and is liable to imprisonment for 2 years.

What follows, in my view, is that if paramedics are called to a person in mental health crisis, the paramedics can give treatment in accordance with ambulance clinical practice guidelines on the basis that they are authorised by ss 25 and 259 and to the extent that the treatment and transport of the person is necessary to protect their life they are duty bound to do so by s 262. It should be noted that the use of sedation would need to be for the benefit of the patient, not the mere convenience of the paramedics.

However to detain and treat a person who is competent and who has refused treatment is an offence. Equally where a person is subject to the care of a medical practitioner and is being treated under the Mental Health Act then it may also follow that care by paramedics may be contrary to the Act. For example if a doctor has determined in accordance with the Act that involuntary treatment is necessary but that this does not require sedation then a paramedic’s choice to sedate the patient would not be treatment in accordance with the Act.

Conclusion

To make my conclusion clear, I agree with the advice from St John (WA) that paramedics do not have an independent authority to sedate a patient where that patient is being treated by medical practitioners and a transport order has been made under the Mental Health Act. In those circumstances the authority to sedate the patient would depend on the patient’s consent or the doctor’s decision to provide emergency psychiatric care if the patient has refused consent or is unable to consent.

I do not think the circular applies, nor does it claim to apply, where paramedics are first responders to a mental health emergency. In those circumstances the paramedic’s authority to administer treatment is found in the Criminal Code (ss 25, 259 and 262) and if it’s relevant the common law of necessity but that is only true if the person is unable to consent to treatment. If the person is competent, even if mentally ill, then it is the police that have the authority to detain the person and arrange their transport, in cooperation with ambulance, to a mental health facility.

Having said that if the person is posing an immediate threat to themselves or others, a paramedic as can anyone, can use force to restrain the person pending arrival of police (ss 25 and 243). I don’t see why force does not extend to sedation but that could be an arguable point. If police were delayed and it was necessary to seek urgent care, I would suggest that ss 25 and 243 would also allow paramedics to transport the person to hospital rather than waiting an extended time for police particularly if that posed a risk to the patient’s mental or physical health.

The same provisions must also apply if there is no authority from a doctor during a hospital transfer and the patient’s condition deteriorates in way that was unforeseen and the patient is now posing a threat to him or herself or the paramedics.

If transporting a patient on a transport order who suddenly becomes aggressive and poses a danger to the crew would it be possible to sedate the patient using S243 CC if that was reasonable and necessary in the circumstances. I’m talking about a sudden change when it is not possible to get authorisation from a Dr to sedate. In short would the CC trump the MHA in this case.

I would think that the criminal code s 243 (quoted in the post), the doctrine of ‘necessity’ and the law of self defence (Criminal Code s 248) would all justify the use of sedation if it was clinically indicated and appropriate in those circumstances.