A correspondent has brought an English case to my attention and says:

Although it relates to the UK and to a doctor it could have salient lessons for paramedics when they become registered… it raises some good debating points around organisational vs personal responsibility.

The story is set out in the link. below:

The gist of the story is that Dr Hadiza Bawa-Garba was ‘convicted of manslaughter on the grounds of gross negligence’ and given a 24-month suspended sentence. She was also suspended from practice as a medical practitioner for 12 months. The General Medical Council (the GMC) appealed to the High Court which upheld the appeal and ordered that Dr Bawa-Garba be struck off the medical register. (Note that in the UK the High Court might be considered akin to an Australian Supreme Court. In Australia the Supreme courts hear trials of serious cases and hear appeals from lower courts. To confuse things, there is an appeal from an Australian Supreme Court to the High Court of Australia. In the UK there is an appeal from the High Court to the UK Supreme Court).

In trying to understand if this decision has implications for Australian paramedics, we need to consider what is meant by negligent manslaughter and what implications a similar result may have for paramedics when they are registered under the Health Practitioner National Law.

Under Australian common law there are two categories of manslaughter. Voluntary manslaughter where the accused intended to kill the deceased but can take advantage of one of the partial defences – provocation or diminished responsibility (there may be slight variations in the name in the jurisdictions). Involuntary manslaughter is where the accused kills the deceased without intending to kill. Rather the death was due to an unlawful and dangerous act or criminal negligence.

In Nydam v R [1977] VR 430 the Victorian Supreme Court said:

In order to establish manslaughter by criminal negligence, it is sufficient if the prosecution shows that the act which caused the death was done by the accused consciously and voluntarily, without any intention of causing death or grievous bodily harm but in circumstances which involved such a great falling short of the standard of care which a reasonable man would have exercised and which involved such a high risk that death or grievous bodily harm would follow that the doing of the act merited criminal punishment.

In Wilson v R (1992) 174 CLR 313 the High Court of Australia said that ‘For manslaughter by criminal negligence, the test is “a high risk that death or grievous bodily harm would follow”.’

The problem with the test for criminal negligence, ie ‘circumstances which involved such a great falling short of the standard of care which a reasonable man would have exercised … that the doing of the act merited criminal punishment’ is that there is no clear definition of when that arises. It is a question for the jury. One might object that this does not give certainty nor guidance to allow people to know, in advance what the law requires. On the other hand, for those that complain about the judicial system, it is a test that allows the jury, as representatives of the community, to determine whether or not conduct in the circumstances is so gross as to warrant punishment.

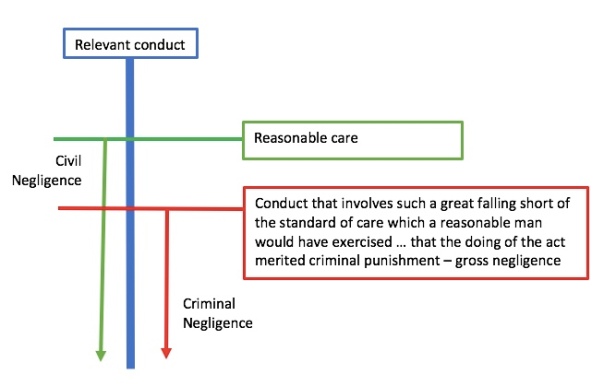

There is a difference between negligence that leads to an order for compensation and criminal negligence. The diagram below may help:

If we consider the relevant conduct, in Dr Bawa-Garba’s case, conduct as a medical practitioner or for this discussion, conduct of a paramedic there is the standard of the ‘reasonable’ practitioner. The ‘reasonable’ practitioner is not necessarily the best so there is conduct above and beyond the reasonable standard, but the minimum expected is ‘reasonable’ performance, as shown by green line above. Where a person fails to perform at that reasonable standard and causes damage to a person to whom they owed a duty of care then that would be the tort (or wrong) of negligence. The negligent practitioner would be liable to pay compensation for that loss but as noted in earlier posts, where the person is an employee, it is their employer that is liable. Also, one can insure against liability to pay damages in tort so it is very rare that the defendant pays damages for negligence. It is either their own, or their employer’s insurer, that pays.

Where conduct amounts to gross negligence (the red line, above) the negligence moves to the criminal sphere. At this point there is no vicarious liability (your employer can’t go to gaol on your behalf) nor can one insure against the risk (your insurance broker won’t go to gaol on your behalf, either). In criminal negligence the Crown must prove the case beyond a reasonable doubt and the sentence imposed by the Court is intended to punish and deter the offender, and others. It is not an order to pay compensation to any one that is injured.

For those interested, you can read the decision of the UK Court of Appeal – Bawa-Garba v R [2016] EWCA Crim 1841 – that upheld her conviction of manslaughter. The facts of that case aren’t however vital for this discussion. For Australian paramedics what needs to be considered is there some conduct that a paramedic could engage in that is so far below the standard to be expected of the reasonable paramedic to warrant criminal punishment? One can imagine giving the wrong drugs, asking the spinal injury patient to walk or the like. I’ll leave to clinicians reading this blog to consider what might meet that threshold test of conduct that involves ‘such a great falling short of the standard of care which a reasonable [paramedic] would have exercised and which involved such a high risk that death or grievous bodily harm would follow that the doing of the act merited criminal punishment’. It is likely to be conduct that you think ‘no-one would do that’ but that is of course the point. The conduct that everyone thinks ‘no-one would do that’ is the type of conduct that is criminally negligent when someone does.

The first conclusion is, therefore, that although it’s hard to imagine the circumstances where it would arise it is indeed theoretically possible that in the right circumstances, a paramedic could be guilty of manslaughter by criminal negligence (as may anyone).

So what does it mean if a paramedic is convicted of this offence and what difference will registration make? One can assume that a paramedic was convicted of manslaughter by criminal negligence he or she would be likely to lose his or her job as a paramedic. I can’t imagine that an ambulance service could defend retaining the employment of a paramedic who had been found, beyond reasonable doubt, to have contributed to a patient’s death due to gross negligence. One can also, I think reasonably, assume that a paramedic convicted of that offence would have difficulty finding ongoing employment with another ambulance service given that conviction.

What different will registration make? Under the Health Practitioner National Law ‘unprofessional conduct’ includes ‘the conviction of the practitioner for an offence … the nature of which may affect the practitioner’s suitability to continue to practise the profession’ (s 5). Conviction of negligent manslaughter would fit that definition. Professional misconduct is ‘unprofessional conduct by the practitioner that amounts to conduct that is substantially below the standard reasonably expected of a registered health practitioner of an equivalent level of training or experience’ (s 5). By definition, criminal negligence requires conduct substantially below the standard expected of a reasonable health practitioner and relevantly in this context, a reasonable paramedic.

A paramedic convicted of manslaughter by gross negligence could also expect to be subject to disciplinary proceedings (s 243) and, like Dr Bawa-Garba, could expect to be suspended or struck off. However, there are advantages for everyone.

In the absence of registration, a paramedic convicted for example in Queensland may lose his or her job with QAS but may get a job with Tasmania Ambulance as Tasmania Ambulance may not be aware of that conviction. There is no central place where that conviction is recorded. That may be unlikely if the paramedic needs to apply for a police check, but it is possible. If the prosecution is known, the paramedic could expect to never work as a paramedic again.

With registration then, to continue my example, Tasmania Ambulance could verify that the paramedic has been suspended or struck off by checking the paramedic’s registration so there would be less risk of the paramedic slipping through the cracks in the process. For the paramedic, if they are suspended they know when they will be able to return to their profession. Even if they are ‘struck off’ it is not necessarily forever. In due course the paramedic (like Dr Bawa-Garba) could apply again to be registered if he or she could show that there has been a sufficient time and circumstances that would satisfy the relevant board that the person is not a risk to the community and in all the circumstances, can show that they are again a fit and proper person to be registered. Once registered by the relevant Board, one would anticipate that an employer could look beyond the earlier conviction given the Board has determined that the person is again fit to practice. That is not to say that would be an easy process or that a person could re-register, but at least it is an option.

The impact of the jury’s decision

There is one issue in Dr Bawa-Garba’s case that I think my correspondent particularly wants me to address. The issue is the role of institutional or system contribution to the outcome. There were systemic failings and Dr Bawa-Garda argued that these were the cause of the poor outcome but this was rejected by the jury as shown by their decision to convict her.

On the question of the appropriate professional penalty, Counsel for the GMC said (General Medical Council v Dr Bawa-Garba [2018] EWHC 76 (Admin), at [26]) ‘the Tribunal had in effect allowed evidence of systemic failings to undermine Dr. Bawa-Garba’s personal culpability, and to do so even though those failings had been before the Crown Court which convicted her…’ That is when determining to suspend her, the Tribunal accepted arguments that the jury had rejected.

Mr Justice Ouseley concluded that the Tribunal had made an error and that Dr Bawa-Garba must be struck off the register of medical practitioners. He said (at [38]):

Full respect had to be given by the Tribunal to the jury’s verdict: that Dr. Bawa-Garba’s failures that day were not simply honest errors or mere negligence, but were truly exceptionally bad. This is no mere emotive phrase as one witness, Dr. Barry, before the Tribunal appeared to suggest, nor were her mistakes mere mistakes with terrible consequences. The degree of error, applying the legal test, was that her own failings were, in the circumstances, “truly exceptionally bad” failings. The crucial issue on sanction, in such a case, is whether any sanction short of erasure can maintain public confidence in the profession and maintain its proper professional standards and conduct. We consider that Mr Hare is right that the Tribunal’s approach did not respect the true force of the jury’s verdict nor did it give it the weight required when considering the need to maintain public confidence in the profession and proper standards.

And later (at [41]):

… a fair reading, shows that the Tribunal did not respect the verdict of the jury as it should have. In fact, it reached its own and less severe view of the degree of Dr. Bawa-Garba’s personal culpability. It did so as a result of considering the systemic failings or failings of others and personal mitigation which had already been considered by the jury; and then came to its own, albeit unstated, view that she was less culpable than the verdict of the jury established. The correct approach, however, enjoined by R34 of the Rules, is that the certificate of conviction is conclusive not just of the fact of conviction (disputed identity apart); it is the basis of the jury’s conviction which must also be treated as conclusive, in line with what the Rule states about Tribunal findings. Mr Larkin did not dispute that the Tribunal had to approach systemic failings or the failings of others on the basis that, notwithstanding such failures, the failures which were Dr. Bawa-Garba’s personal responsibility were “truly exceptionally bad”, and those are summarised in the judgment of the CACD. Although Mr Larkin is right that such factors may reduce her culpability, they cannot reduce it below a level of personal culpability which was “truly exceptionally bad”. The Tribunal had to recognise the gravity of the nature of the failings, (not just their consequences), and that the jury convicted Dr Bawa-Garba, notwithstanding those systemic factors and the failings of others, and the personal mitigation it considered. The jury’s verdict therefore had to be the basis upon which the Tribunal reached its decision on sanction.

The implication of this part of the decision is not directly applicable to Australian paramedics. The extent to which a tribunal in Australia could make decisions that might be inconsistent with a jury’s verdict will eventually depend on the rules promulgated by the relevant board. One can expect however that where, in disciplinary proceedings, it is alleged that the paramedic’s conviction is what constitutes unprofessional conduct/professional misconduct then it would have to be the case that it is the facts as found by the jury that are relevant in determining whether that conviction does or does not demonstrate unprofessional conduct or professional misconduct. If the ‘prosecution’ is relying on the conviction the Tribunal would have to look at the conviction and facts as found by the jury. It could not dismiss the case on the basis that the Tribunal would not have convicted the practitioner. It is the conviction, and therefore the facts that form the basis of that conviction, that constitute unprofessional conduct so it can’t be open to the Tribunal to find that the facts established by the jury are not the facts to determine the professional sanction.

Conclusion

My conclusions are:

- A paramedic could be convicted of manslaughter by criminal negligence but I can’t really imagine an appropriate example where that may arise.

- Whether there is registration or not, a paramedic would expect to lose their ability to practice as a paramedic. At least with registration the fact that the paramedic has been ‘struck off’ could be verified by any potential employer and so ensure that the person can’t slip through and get another job in another jurisdiction. Further it may open to the door to a return to practice if, after a sufficient time, the paramedic can convince the Board that he or she is again a fit and proper person to practice.

- Where a person is convicted and professional disciplinary action is commenced on the basis of that conviction, the relevant decision maker would have to make a decision consistent with the conviction and could not find or base the decision on a view of the facts that is inconsistent with that verdict. The exact reasoning in General Medical Council v Dr Bawa-Garba [2018] EWHC 76 (Admin) would not apply in Australia as it is an English case and the rules of Paramedicine Board are not going to be exactly the same as the Sanctions Guidance issued by the GMC but the general principle will still apply where the conviction is the basis of the complaint of professional misconduct. The decision maker will have to accept the facts are as determined by the jury.