Today’s correspondent, from Victoria, has a

… question about the management of a patient who has a valid ACD stating they are not for resuscitation, post attempted suicide.

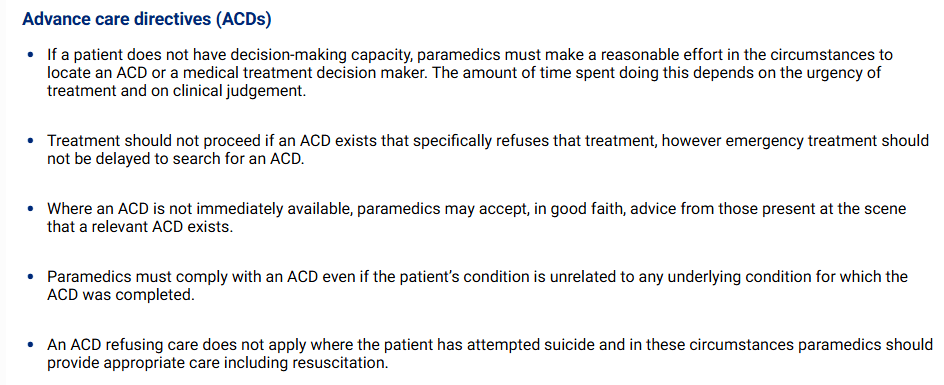

My thoughts were that if an ACD is valid, and available, then it should be followed despite the cause. However I note the Ambulance Victoria CPG A0111 [available at https://cpg.ambulance.vic.gov.au] states the following:

Advance Care Directives are provided for in the Medical Treatment Planning and Decisions Act 2016 (Vic). An advanced care directive comes into force when it is signed and remains in force until any expiry date specified or the person dies (s 19). Section 60 says:

(1) If a health practitioner proposes to administer medical treatment to a person who has an advance care directive and the person does not have decision-making capacity in respect of that medical treatment, the health practitioner must, as far as reasonably practicable—

(a) subject to section 51, give effect to any relevant instructional directive by—

(i) in the case of an instructional directive refusing particular medical treatment, withholding or withdrawing that medical treatment; and

(ii) in the case of an instructional directive consenting to particular medical treatment, administering that medical treatment if the health practitioner is of the opinion that it is clinically appropriate to do so; and

(b) in the case of an advance care directive that does not include a relevant instructional directive, refer any medical treatment decision to the person’s medical treatment decision maker for a decision under section 61; and

(c) consider any values directive in offering and administering medical treatment.

(2) If a registered health practitioner contravenes subsection (1), that contravention is unprofessional conduct.

Section 51 says:

A health practitioner may refuse under this Part to comply with an instructional directive if the health practitioner believes on reasonable grounds that—

(a) circumstances have changed since the person gave the advance care directive so that the practical effect of the instructional directive would no longer be consistent with the person’s preferences and values; and

(b) the delay that would be caused by an application to VCAT under section 22 would result in a significant deterioration of the person’s condition.

Section 53 says:

(1) Subject to subsection (2), a health practitioner may administer medical treatment (other than electroconvulsive treatment) or a medical research procedure to a person without consent under this Part or without consent or authorisation under Part 5 if the practitioner believes on reasonable grounds that the medical treatment or medical research procedure is necessary, as a matter of urgency to—

(a) save the person’s life; or

(b) prevent serious damage to the person’s health; or

(c) prevent the person from suffering or continuing to suffer significant pain or distress.

(2) A health practitioner is not permitted to administer medical treatment or a medical research procedure to a person under subsection (1) if the practitioner is aware that the person has refused the particular medical treatment or procedure, whether by way of an instructional directive or a legally valid and informed refusal of treatment by or under another form of informed consent.

It should be noted that suicide is no longer a crime (Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) s 6A). Even so s 463B says:

Every person is justified in using such force as may reasonably be necessary to prevent the commission of suicide or of any act which he believes on reasonable grounds would, if committed, amount to suicide.

That section give immunity from criminal law ie it is not an assault (Stuart v Kirkland-Veenstra [2009] HCA 15, [43] (French CJ) to try and stop someone jumping in front of a train. But, said French CJ, ‘It was not suggested that it had any part to play in determining whether officers Stuart and Woolcock owed a legal duty of care to the deceased and his wife’. Just as the question of the police officer’s duty to Mr Veenstra who had been contemplating suicide was not determined by s 463B, so too a doctor’s or paramedic’s duty to their patient will not be determined or should not be determined by that section. The health practitioner’s duty is to respect their patient’s autonomy and not to provide care that the person has expressly refused relying on a statute that has been put in place specifically to allow a person to give or refuse consent.

Whether it is ‘reasonably necessary’ to impose treatment on someone who has, relying on the Medical Treatment Planning and Decisions Act 2016 (Vic) specifically refused that very treatment is debatable. How can it be reasonable to impose treatment that a person has specifically said they don’t want? Remember that ‘The common law does not … support the general proposition that attempted suicide or suicide gives rise to a presumption of mental illness’ (Stuart’s case [46] and [54] (French CJ). When talking about the Mental Health Act 1986 (Vic) s 10 (now repealed) Crennan and Kiefel JJ said (at [147]):

Depending on the circumstances, a person who has attempted, or is likely to attempt, suicide may or may not satisfy the criteria of mental illness… The purpose of s 10(1) is to allow officers lawfully to apprehend a person who appears to be mentally ill and is also at risk of harm. Its purpose is not to prevent suicide. In this regard the Act does not deviate from the common law view of autonomy.

Of course, every case needs to be judged on its facts. The attempted suicide may appear quite inconsistent with the person’s stated wishes for example if they indicated they don’t want to be resuscitated if they reach a certain level of incapacity then a suicidal action when they are no-where near that level may give rise to a view that their circumstances (eg their mental health) have changed such that they would not want to the direction to apply in this case at this time. But in in other cases, a person who has made an ACD specifically refusing life sustaining or life saving treatment and then takes steps to end their own life, their actions and the ACD may be quite consistent and consistent with a rational decision-making process.

Discussion

There is nothing in the Act that says an ACD does not apply if the patient is intending to take their own life. Some would think that a decision to refuse treatment where without that treatment a person will die is itself suicide but that is what is intended by all the legislation allowing advance care directives.

The ethical principle of respect for autonomy says that patient’s wishes have to be respected and that is most important when the decisions are about life and death and where the decision is against the health practitioner’s assessment of what is in the patient’s best interests. But if consent is only required when the doctor or paramedic agrees with the decision then consent is trivial.

Respect for autonomy says the patient gets to decide. And if the patient has executed an instructional directive (s 6) that is an express refusal of some form of treatment, then provided the person met the conditions for a valid ACD that is binding even if the proposed treatment is necessary to save the patient’s life (s 53(2)).

A patient may use an Advance Care Directive to refuse treatment with sure and certain knowledge that without that treatment, they will die; eg a patient might refuse kidney dialysis even though with dialysis the may live for many years. It would be an affront to the principle of autonomy to force dialysis on them because without it they will die and that constitutes ‘suicide’.

It might be argued that there is a passive/active distinction, that is it is not suicide to refuse treatment and to let oneself die but it is to take active steps to hasten one’s own death but the patient who refuses dialysis knows they will die and intends that they will die with same surety as someone who takes an overdose of medication or shoots themself in the head. Arguing you cannot impose treatment on one but not on the other makes no-sense.

In any event the provisions of the Crimes Act may mean there is no criminal penalty, but it does not mean that a health practitioner has acted ethically and is not subject to disciplinary proceedings if they fail to honour an advance care directive.

Conclusion

There is nothing in the Act to say that the fact that the person has attempted suicide is in any way relevant to the application of their ACD. It may be relevant to the question of whether ‘circumstances have changed since the person gave the advance care directive so that the practical effect of the instructional directive would no longer be consistent with the person’s preferences and values’ but it is not a single determining fact. The Act does not say that an ACD does not apply if the person has attempted suicide. It says it does apply even if the treatment that has been refused is necessary to save the patient’s life.

This blog is made possible with generous financial support from (in alphabetical order) the Australasian College of Paramedicine, the Australian Paramedics Association (NSW), the Australian Paramedics Association (Qld), Natural Hazards Research Australia, NSW Rural Fire Service Association and the NSW SES Volunteers Association. I am responsible for the content in this post including any errors or omissions. Any opinions expressed are mine, and do not necessarily reflect the opinion or understanding of the donors.

This blog is a general discussion of legal principles only. It is not legal advice. Do not rely on the information here to make decisions regarding your legal position or to make decisions that affect your legal rights or responsibilities. For advice on your particular circumstances always consult an admitted legal practitioner in your state or territory.

Interesting that they have a clause in the protocol related to suicide but not homicide or any other cause of incapacity. Would this be read that if a family member stated they had administered the overdose which caused the incapacity the ACD would be respected?