Today’s correspondent continues the discussion about the role of hospital security staff. My correspondent is concerned that:

… nursing staff are receiving handover and taking over patients who are being bought in under schedule (Mental Health Act) schedule 1, section 20 or section 22 though the patient is noted to be in Police custody, we have been told by our management that police can handover a patient in custody if the clinician is willing to accept the patient and we then contact the police back after the patient has been dealt with under the Mental Health Act and/or assessed. We have never had this issue with previous management as Police were always to stay with the section patient who was in custody up and until they were assessed by the hospital psychiatrist and admitted to the mental health unit otherwise the police were to remain with the patient at all times and the patient was not to be handed over to the hospital due to the patient being in custody?

I am asked to ‘please provide some clarification on this above matter’.

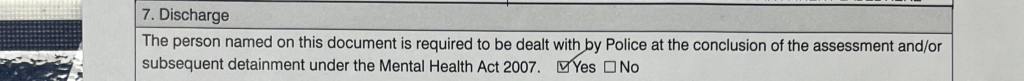

My correspondent provided this screen shot of some relevant paperwork:

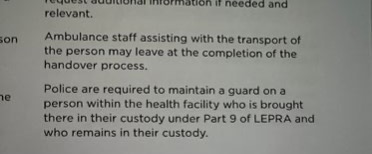

Along with these instructions:

The Mental Health Act

The Mental Health Act 1987 (NSW) s 18(1) says:

A person may be detained in a declared mental health facility in the following circumstances–

(a) on a mental health certificate given by a medical practitioner or accredited person (see section 19),

(b) after being brought to the facility by an ambulance officer (see section 20),

(c) after being apprehended by a police officer (see section 22)…

Where my correspondent refers to schedule 1 that is actually a reference to the form that a doctor must complete in order to authorise a person’s detention eg where a GP has examined a patient and forms the view they should be examined by a psychiatrist and detained until that can happen. The question, more accurately, should say ‘… patients who are being bought in under sections 19, 20 or 22 …’.

A person may be having a mental health crisis and be observed by a doctor, an ambulance officer, or a police officer. A doctor may elect to write a certificate whilst an ambulance or police officer may elect to transport the person to a declared mental health facility. Where a doctor has written a certificate, they may endorse the certificate to the effect that police assistance is required (s 19(3)). Ambulance officers may also request police assistance (s 20(2)). Where a doctor or an ambulance officer has requested police assistance, that assistance must be provided (s 21).

It follows that the police can become involved at the request of a doctor or ambulance officer or on their own initiative. Police may become involved if a mentally ill person is or may be committing a crime. The police may be called and form the view that the person may be mentally ill and that it would be better for everyone if they were dealt with as a patient rather than as a criminal.

Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act (LEPRA)

Apart from the power to detain under s 22, above, police as law enforcement have the power to arrest as part of the processes of the criminal law. The Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW) (LEPRA) s 99(1) says:

A police officer may, without a warrant, arrest a person if–

(a) the police officer suspects on reasonable grounds that the person is committing or has committed an offence, and

(b) the police officer is satisfied that the arrest is reasonably necessary for any one or more of the following reasons–

(i) to stop the person committing or repeating the offence or committing another offence,

(ii) to stop the person fleeing from a police officer or from the location of the offence,

(iii) to enable inquiries to be made to establish the person’s identity if it cannot be readily established or if the police officer suspects on reasonable grounds that identity information provided is false,

(iv) to ensure that the person appears before a court in relation to the offence,

(v) to obtain property in the possession of the person that is connected with the offence,

(vi) to preserve evidence of the offence or prevent the fabrication of evidence,

(vii) to prevent the harassment of, or interference with, any person who may give evidence in relation to the offence,

(viii) to protect the safety or welfare of any person (including the person arrested),

(ix) because of the nature and seriousness of the offence.

Section 105 says:

(1) A police officer may discontinue an arrest at any time.

(2) Without limiting subsection (1), a police officer may discontinue an arrest in any of the following circumstances–

(a) if the arrested person is no longer a suspect or the reason for the arrest no longer exists for any other reason,

(b) if it is more appropriate to deal with the matter in some other manner…

Discussion

It is the interplay of the powers of arrest and the Mental Health Act that concerns my correspondent.

Let us assume that a police officer is called to a scene where a person who ‘appears to be mentally ill or mentally disturbed’ has engaged in conduct that, on its face, appears to be criminal eg they have damaged someone’s property or injured another person. The police officer may well decide to make an arrest as they have the suspicion required by s 99(1)(a) and they form the view that the arrest is warranted by virtue of ss 99(1)(b)(i), (ii) and (viii).

Having made the arrest and taken the person into custody there is now no immediate threat that the offending will continue, and the victim is no longer at risk. The officer now needs to decide whether to proceed along the criminal route, which would involve things like taking the person back to the police station to be interviewed, considering whether the person can be released either on bail or own their own undertaking and issuing a court attendance notice. The officer may be aware that if the person is indeed mentally ill they may not be criminally responsible for their conduct, and a prosecutor should only proceed if there are reasonable prospects of success so a determination of the person’s mental health status is important. Also, if the person is mentally ill it would be beneficial for them and the community that their underlying health issues are dealt with.

The police officer may then form the view that it would be more appropriate (s 105(2)(b)) to deal with the person under the Mental Health Act, so they proceed to take the person to the declared mental health facility relying on s 22. Given the person may be detained at the mental health facility it is appropriate to terminate the arrest on the grounds set out in s 105(2)(a) and (b)). At that point that the person is being detained by the mental health facility there is no need or authority for police to stay to maintain the person’s custody.

Police can ask, as they do, that if the person is to be discharged that they want to know so they can again revisit the decisions. If the psychiatrist assesses the patient and determines they are not mentally ill or do not meet the criteria for involuntary admission, the police may want to proceed with criminal proceedings.

LEPRA Part 9

The discussion above is not inconsistent with the instruction that:

Police are required to maintain a guard on a person within a health facility who is brought there in their custody under Part 9 of LEPRA and who remains in their custody.

Part 9 of LEPRA deals with investigation and questioning. It allows police to detain a person, without charge, whilst certain investigations are complete. Whilst being so detained a person has a right to medical attention (s 129). Section 138 says:

A medical practitioner acting at the request of a police officer of the rank of sergeant or above, and any person acting in good faith in aid of the medical practitioner and under his or her direction, may examine a person in lawful custody for the purpose of obtaining evidence as to the commission of an offence if–

(a) the person in custody has been charged with an offence, and

(b) there are reasonable grounds for believing that an examination of the person may provide evidence as to the commission of the offence.

One can imagine that a prisoner may be brought to the hospital because they require medical attention or the police want an examination to collect evidence eg an x-ray to see if the person has swallowed drug packets, or a blood test etc. It is in those circumstances, where the arrest is continuing and the whole point of the exercise may be the collection of evidence, that it is police who must maintain the custody of the person.

A person who has been brought to a hospital under s 22, even if they had been arrested, is not a person in police ‘custody under Part 9 of LEPRA’.

The view of ‘previous management’

What concerns me is the final statement of the original question:

We have never had this issue with previous management as Police were always to stay with the section patient who was in custody up and until they were assessed by the hospital psychiatrist and admitted to the mental health unit otherwise the police were to remain with the patient at all times and the patient was not to be handed over to the hospital due to the patient being in custody?

Why it concerns me is that, reading between the lines, it implies a misunderstanding of what custody means and the role of police and the health facility and that is a worry if that misunderstanding was held, and promoted by ‘previous management’.

A person who is brought in under s 22 is not in police custody. They have been detained for the purpose of taking them to a health facility for care. The police detention ends when the person is delivered to the care of the facility, not on assessment by a psychiatrist. If the person has been arrested that arrest can, and should be, terminated whilst the person is being detained in the health facility for the reasons set out in s 105 of LEPRA.

A person who is brought into a declared mental health facility by police acting under s 22 can be detained at the facility for up to 12 hours (Mental Health Act 2007 (NSW) s 27(1)(a)). If there is a secured mental health ward the person could be located there without first being seen by a psychiatrist, that is the whole point of ss 19 and 22. The person can be detained on the basis of the information provided by police alone. It would be a waste of police and community resources to take police away from their other duties for up to 12 hours when a declared mental health facility should have the facilities to detain people.

Using police to secure the mentally ill is anti-therapeutic. At that time the person is in the care of a health facility for assessment and if necessary, treatment and care. Having uniformed and armed police in the ward would not be good for anyone. Being able to care for people in a secure environment should be part of the core business of a declared mental health facility.

Conclusion

In my view it is not only lawful it is entirely appropriate that ‘police can handover a patient in custody if the clinician is willing to accept the patient and we then contact the police back after the patient has been dealt with under the Mental Health Act’. Such action is consistent with both the Mental Health Act and LEPRA.

This blog is made possible with generous financial support from the Australasian College of Paramedicine, the Australian Paramedics Association (NSW), Natural Hazards Research Australia, NSW Rural Fire Service Association and the NSW SES Volunteers Association. I am responsible for the content in this post including any errors or omissions. Any opinions expressed are mine, and do not necessarily reflect the opinion or understanding of the donors.

Hi Michael,

It is also important to address this in conjunction with the “NSW Health – NSW Police Force Memorandum of Understanding 2018”, which “sets out the principles which guide how agencies will work together when delivering services to people with mental health problems.”

It is concerning that your correspondent has no knowledge of this document, given they purport to have some involvement with Mental Health patients.

In particular Section 3.4 – “ARRIVING AT THE HOSPITAL” gives guidelines for Police and Health staff.

As you state, there is also a clear distinction between a *patient* detained under the Mental Health Act, versus an alleged offender detained under LEPRA (or similar arrest powers).

The MOU is publicly available from both NSW Health and the NSW Police Force.

MOU Source Link:

Click to access MOU_NSWH_NSWPF_Mar18_V5.pdf